Ask anyone with at least one eye on world literature in translation which countries are putting out the most groundbreaking novels, and they will likely mention South Korea. Korean novels frequently bend and break genres, explore often untouched social and political themes, and speak to our very souls.

If you’re looking for the best Korean novels in English translation, this list of ten is the perfect place to start. Many of the Korean authors (and translators) mentioned here have entire libraries available for you to explore once you’ve exhausted this list.

You can also subscribe to the Korean Literature Now Magazine and browse their website to keep with the latest news, poetry, fiction, and articles.

A note on names: In Korea, family names come first, and publishers of Korean novels in translation seem to often disagree over whether or not to flip them for English language readers. Some do, some don’t. You get used to it.

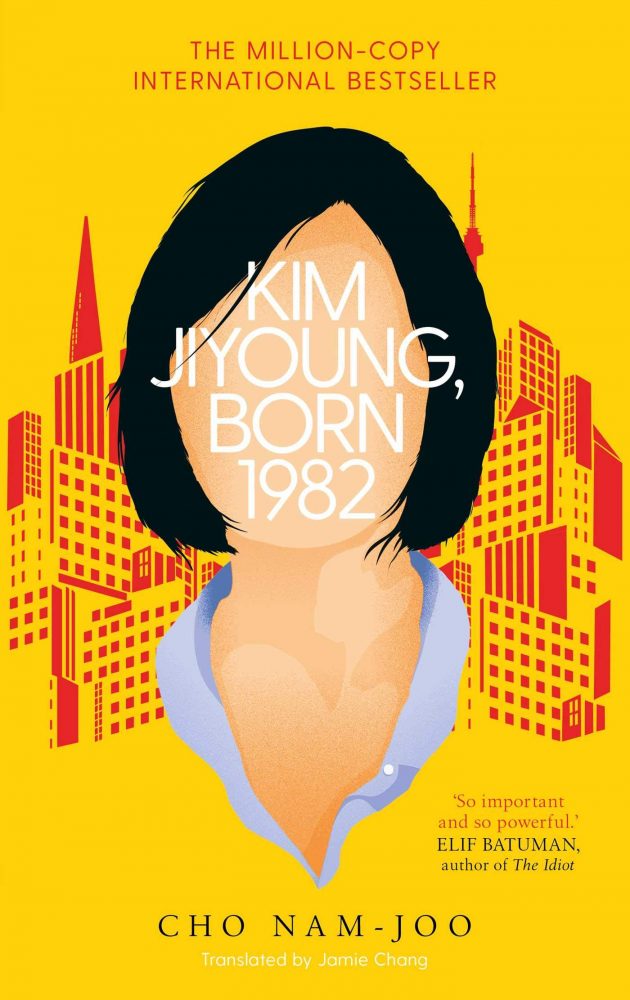

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-joo

Translated by Jamie Chang

Approaching a book like Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is an enormous undertaking; something that should be done with real consideration. The novel has sold over a million copies in its native South Korea, has been adapted into a successful Korean film, and has been a huge spark for the fires of the #metoo movement in South Korea.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is a novel that has achieved so much, done so much good, and is now finally available to English-speaking readers. Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 can be seen as the novelisation of the lived experiences of every ordinary Korean woman for the past forty years. It traces the life of a single woman from early childhood to marriage and motherhood.

The book begins with her being given an appointment with a psychiatrist in 2016 after she has developed a disturbing condition wherein she impersonates the voices of, and embodies the personalities of, the women in her life both alive and dead.

This condition is what initially introduces us to her character, and it is a very clear statement to the reader that Kim Jiyoung speaks for every ordinary woman of 20th and 21st Century South Korea. Everything you may have heard about Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 being an impactful and important piece of feminist fiction is true.

It is a book that brings to light the everyday misogyny, sexism, ignorance, aggression, bias, and abuse (both active and passive) that women in South Korea (and, of course, the world over) suffer and do their best to survive in this modern world.

To really get the most out of Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, one of the most powerful Korean novels, it’s important to first understand the novel’s purpose.

It is not a story with a view to entertaining us. It is a book that enlightens, and encourages anger in, its readers. Kim Jiyoung is not an individual. She is not a character to form a bond with. She is every abuse victim. She is every woman who has encountered sexism at home, at school, in the workplace, and on the street, and who perhaps never even realised it.

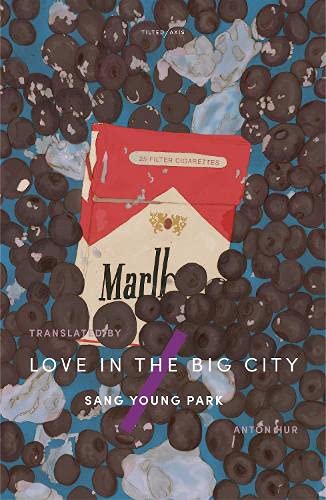

Love in the Big City by Sang Young Park

Translated by Anton Hur

Love in the Big City is a queer Korean love story. It is a tale of hedonism and friendship; a book about looking at life from all angles: with love and hate and anger and fear in our eyes.

Divided into four acts, Love in the Big City begins with Young at university, living his best life with close friend Jaehee. The two of them live together, party hard, sleep around, and look out for one another. But, eventually, Jaehee wants to get married and grow up.

This Korean novel’s second act explores Young’s relationship to his mother, now and in the past, and the third act sees him chasing love, finding it, being let down by it, and finding it again.

Translated elegantly and beautifully by Anton Hur, Love in the Big City considers how we live our lives when time is ticking, when there is fun to be had and things to be seen; when there are things to fear and people who want to hurt us.

This is also a novel full of charming details. Young and Jaehee, in their early days, look out for one another. He keeps her stocked with Marlboro cigarettes and she keeps the fridge full of fruits (blueberries are his favourites). Those details aren’t all positive — the novel doesn’t shy away from moments of pain and fear and difficulty. Young encounters homophobia and his relationship with his mother is strain in more ways than one.

Love in the Big City paints a raw and honest but ultimately kind picture of love and life in the modern day, and for that, it is one of the finest modern Korean novels.

Read More: 12 Best K-Pop Books (For Stans Everywhere)

Violets by Kyung-sook Shin

Translated by Anton Hur

Kyung-sook Shin is one of South Korea’s most beloved and revered authors. One read of Violets and it’s easy to see why. This is a feminist tale about friendship in the modern world, and about the insidious, subtle ways in which men abuse women on a daily basis.

One of the most impactful and changing Korean novels of the past few years, Violets begins with its protagonist, San, as a young girl in 1970. She lives in a small village and is a lonely social outsider.

In the opening chapter, San shares a moment of tender intimacy with her best friend. For San, this is an awakening. For her friend, it is frightening and wrong. They don’t see each other again, and we spend the rest of the novel with San as a twenty-something living in Seoul.

When San takes a job as a florist, she develops a sweet friendship with her coworker, who soon moves in with her. But San is also at the whim of men. She learns how men violate the spaces and bodies of women on a daily basis, in a way that seems almost invisible. Violets has the power to reshape how we all see the social dynamics at play between men and women.

The physical and verbal weapons softly used by men to scare, suppress, and intimidate the women in their lives. It’s a novel that leaves a mark, but also a tender and beautiful narrative.

Watch our full video review of Violets

Greek Lessons by Han Kang

Translated by Deborah Smith & Emily Yae Won

Han Kang is nothing short of a legend of Korean literature. Her novel The Vegetarian, also translated into English by Tilted Axis Press founder Deborah Smith, won the International Booker Prize in 2016 and the rest is history.

The Vegetarian was the first Korean novel that this writer ever read, and that is probably true for many readers. Han Kang and Deborah Smith opened the door for countless English-language readers to become intrigued by, and seek out more Korean literature.

With Greek Lessons, Han Kang is examining and testing the powers of language itself. This short novel follows two protagonists, one of whom is losing his sight and the other is struggling with mutism. Our mute character, an academic and successful writer, has suffered through the loss of her mother, the breakdown of her marriage, and has just lost custody of her child.

She has chosen to enrol in a class to study ancient Greek as a means of reconnecting with language, and by extension, with herself. Her teacher is our other protagonist, a man who spent his youth in Germany and who, therefore, has always felt a cultural disconnect.

His story plays out in the first person, and hers in the third. This is a striking distinction; wordlessly demonstrating how he is stuck in his mind, his memories, and his anxieties. Conversely, she feels a separation, a disconnect from herself, from her experiences — she is floating and alone, cold and confused.

Greek Lessons is a love letter to language as a means of connection, of understanding, of translating our experiences and our feelings in profound and satisfying ways. Han Kang continues to write some of the best Korean books of the modern day, and Greek Lessons is no exception.

Buy a copy of Greek Lessons here!

Walking Practice by Dolki Min

Translated by Victoria Caudle

Walking Practice is an ingenious piece of speculative Korean fiction that blends elements of horror, science fiction, and satire to create something thematically dense, sometimes funny, often shocking, and satisfyingly allegorical.

Across just 150 pages, this Korean novel tells the story of a nameless and genderless alien which crash-landed on Earth fifteen years ago, after fleeing a war that destroyed their homeworld. After surviving off anything they could get their tentacles on, they found that the most satisfying food available was, in, fact, human meat.

And so, for over a decade, they have been disguising themself as men and women, and using dating apps to seduce people, glean some sexual satisfaction (and occasional companionship), before devouring them in a gleefully gruesome manner.

For the novel’s first half, we follow this pattern a few times, and we see the differences in their behaviour when presenting as a man or a woman; how the unspoken rules of society encourage them to behave.

And also how others behave in response to them. This is an explicit examination of patriarchy and the restrictions of gender expression, as well as social relationships between genders. But it goes deeper than this, as our protagonist admits to their loneliness and seeks love, companionship, community, and a sense of belonging.

With smart and satisfying queer allegories aplenty and some truly astonishing and creative translation work from Victoria Caudle, this is one of the best Korean novels of recent years.

Buy a copy of Walking Practice here!

The New Seoul Park Jelly Massacre by Cho Yeeun

Told from multiple perspectives, The New Seoul Park Jelly Massacre provides the reader with what it says on the tin: a massacre about jelly at a theme park in Seoul. We begin with a young girl whose parents don’t get along. She so wishes they did, and when she gets lost in the crowd, the girl meets a man whose face is out of focus, and is offering visitors to the park a jelly sweet that will keep those who eat them bonded forever.

This turns out to be unsettlingly literal, as the jelly sweet causes its consumers to melt into jelly, and their forms begin to melt into one amorphous thing. We then see this gradual massacre play out from different angles: that of a girl in a difficult romance, that of a fed-up employee who wears a mascot uniform, and even that of a successful CEO who is secretly part of a satanic cult.

Thematically, these people represent dissatisfaction, exhaustion, and frustration—in work, love, and life—and the theme park is their place to escape; the place where dreams come true. But things are never that simple, are they?

I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Sehee

Translated by Anton Hur

In her introduction to this incredible book, author Baek Sehee notes that her hope is for people to read this book and think, “I wasn’t the only person who felt like this.” To that end, I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is an exercise in empathy; in the author opening up her chest and letting her darkest feelings tumble out, in the hope that you will feel understood.

Depression is isolating, frightening, and draining. Knowing there’s someone else out there who has felt this way — who still feels this way — can be incredibly comforting.

I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is unique amongst these other Korean novels in that it isn’t actually a novel, but rather a kind of epistolary narrative that tracks a woman’s life through therapy. Most chapters begin and/or end with a confession: a personal experience or a feeling related to the author’s depression and anxieties. The rest of the chapter is a transcript of a therapy session.

These sessions divulge personal experiences and opinions, and also provide us with advice and understanding from the therapist as they listen to the author’s experiences. It feels very voyeuristic, getting to know this author’s inner thoughts and feelings so intimately, but the sense of companionship that comes from it all is so appreciated.

Writing something so revealing and honest must have taken incredible courage, but Baek Sehee has done so with the selfless desire to help others feel less alone and unique in their pain. If you struggle with depression, or know someone who does, I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki is a lesson in empathy and a hug from a comrade-in-suffering.

The Plotters by Un-su Kim

Translated by Sora Kim-Russell

The most important thing to note about The Plotters is that it’s billed as a thriller, but it is actually far more than that. Rather than blending genres and emerging as a kind of Frankenstein’s Monster of different styles, The Plotters rather refuses to acknowledge genre.

The Plotters tells the story of Reseng, a successful assassin raised in The Doghouse Library – a library filled with books but empty of people, somewhere in Seoul – by an enigmatic old man known as Old Raccoon. Reseng has grown up knowing of nothing but the business of assassination, and curiously also knowing very little about that, either.

This is a piece of penetrating fiction driven by its eccentric but grounded characters, providing a unique and entertaining setting and circumstance, and telling a story subtly tied to the history and politics of modern day Korea. After the Korean War and the separation of the two Koreas along the thirty-eighth parallel, control of North Korea was seized by the Kim regime.

What is lesser-known, however, is that South Korea too did not have democratic freedom until the 1980s, suffering through martial law for some decades. This key aspect of Korean history plays into the story of The Plotters, as the democratisation creates a power struggle amongst assassins and leaves room for a different kind of man to take charge.

Blending this wild and wonderful story of assassins who work from an old library with real-world political events allows for some subtle commentary on the nature of fascism, martial law, democracy, and even capitalism, with regards to how these things affect the kinds of lives people can lead. Even assassins are not immune to political shifts.

The Plotters is one of the most ambitious Korean novels; something that has to be read to be believed. Its ability to defy genre, allow its plot to be carried along by comedy and eccentric characters, and keep a slow pace that takes time without losing momentum is truly staggering.

It takes influence from the tumultuous events of South Korea’s recent past without becoming dry and melancholy. Most importantly of all, it is fantastically fun.

Buy a copy of The Plotters here!

The Cabinet by Un-su Kim

Translated by Sean Lin Halbert

Un-su Kim’s The Cabinet is a fantastic and engaging blend of speculative short stories and a longer, underlying thread. Our protagonist, Mr. Kong, is a simple office worker who has wound up as the caretaker of a filing cabinet full of accounts of strange people known as “symptomers”: human beings with odd conditions and abilities.

The novel contains many stories dedicated to symptomers: a man with a gingko tree growing out of his finger; people who seem to jump forward in time at random; people who sustain themselves off glass, steel, or gasoline. These stories make up half the narrative, and paint a vivid picture of a world that is far stranger than what we see and believe in our day-to-day.

The broader narrative is about Kong himself. We gradually learn about his life, his boss, his childhood, how he ended up in this position. There is a mystery to uncover here, and as the novel progresses, that mystery gradually unfolds in an addictive, tantalising, and strange way.

The Cabinet is a work of boundless imagination, written by a beloved Korean author and translated brilliantly by Sean Lin Halbert.

Buy a copy of The Cabinet here!

Tower by Bae Myung-hoon

Translated by Sung Ryu

Tower is a truly unique and boundary-pushing piece of Korean science fiction. When we look at Korean novels in translation, too few of them are genre fiction. But that is slowly changing, and Tower is a Korean book you need to pick up and read.

As its name implies, this piece of Korean sci-fi is set entirely in an enormous tower. This titular tower is a nation unto itself, home to 500,000 people. Bae implies that it was built on Korean soil but this is never explicitly stated. The book is divided into a series of interconnected speculative tales, all set within this solitary tower nation known as Beanstalk.

The world-building is fantastic, as the tower needs to be a believable place in order for the author’s disparate tales to work. Infrastructure, economy, politics, and daily life all need to be accounted for and designed in a way that the reader can understand and appreciate.

The six stories in Tower are tied together by the place itself and by recurring characters and events. And each story serves to further build the world while also telling an entirely self-contained tale. In that sense, this is a unique piece of Korean fiction that blends the concepts of the novel and the short story collection.

And each tale also, as all good science fiction does, poses an ethical, political, or philosophical quandary for us to muse over.

Blood of the Old Kings by Sung-il Kim

Translated by Anton Hur

So often, the novels we come to expect to see translated from Korean into English are literary novels set in our modern day; bold and challenging works that are inherently tied to the modern Korean experience. And while it is always important to have these groundbreaking works of fiction in translation, it is also exciting to see the shift towards receiving more genre fiction: fantasy, horror, romance, and sci-fi.

Blood of the Old Kings is very much a breath of fresh air in that regard—an epic fantasy novel that leans into the classic tropes of the genre (magic swords, dragons, rebellions, and quests) while also providing readers with a powerful connection to real-world politics through an allegory concerning colonialism and empire.

Three unconnected characters—one who receives a sword from a dragon, another who studies magic and whose mind is suddenly invaded by a strange voice, and a third who is investigating the death of his friend—embark on missions that will eventually see them crossing paths as they take steps to rise up against the empire that annexed their nation. A thrill ride of a Korean fantasy novel.

I’m Waiting for You by Kim Bo-young

Translated by Sung Ryu and Sophie Bowman

With the spread of Korean science fiction into the West, through the hard work of talented and dedicated translators like Ryu and Bowman, we get incredible gems like this one. I’m Waiting for You is one of the best Korean novels published in the past few years. Here’s why.

Kim Bo-Young is a legend of Korean literature, and even worked as a script editor on Oscar-winning director Bong Joon-Ho’s Snowpiercer. With I’m Waiting for You, readers can see first-hand why she’s such a special sci-fi author. This collection of four stories is essential reading amongst sci-fi books by women writers.

The four stories in this collection actually work as two pairs. The first and fourth stories — I’m Waiting For You and On My Way to You — are the same tale told from two perspectives: a bride and groom each making their way home to Earth for their wedding ceremony.

The second and third stories — The Prophet of Corruption and That One Life — also the longest and shortest tales respectively, blend religion, mysticism, and science fiction. In these two middle tales, the characters are a set of gods, and it is quickly revealed that they created Earth as a school in which they themselves can learn and grow.

The main protagonist of The Prophet of Corruption, Naban, is a single god whose prophets, disciples, and children all separated from them like cells. Individually, they spend entire lifetimes on Earth, learning and experiencing and dying.

Naban believes in asceticism as a school of learning; their children are reborn in low roles; they suffer and toil and eventually return home. But some are rebelling against this approach to living and learning. What makes these stories so tantalisingly addictive is Kim’s world-building and her attempt at writing gods as characters, with motivations and behaviours different from our own.

The stories that bookend this collection are each written in an epistolary fashion, as letters to the other. In I’m Waiting For You, our nameless groom is trying to make it to Earth, and is updating his bride each time something goes awry (and a lot goes awry).

The same is true in On My Way to You; the bride has her own hurdles to overcome. These two stories are heartbreaking. You’ll root for them, cry for them, hope against hope that things will work out for them.

Your Utopia by Bora Chung

Translated by Anton Hur

From the author of the wonderfully strange, exciting, and diverse Cursed Bunny, Your Utopia is a science fiction short story collection. The protagonists of this collection vary from far-future space-faring humans to artificially intelligent cars and sentient elevators.

Though these stories are all within the realm of science fiction, they explore an enormous spectrum of style and tone. One story, Seed, is a bleakly funny satire that observes a conversation between a copse of trees and a handful of eugenics-made humans. Another, A Very Ordinary Marriage, follows a newly-married man who becomes paranoid when he catches his wife making secretive phone calls in a language he has never heard before.

The sheer amount of scope and variety in these stories wonderfully showcases the potential of science fiction to tell stories that make readers laugh, scream, and cry. Bora Chung is one of the most imaginative Korean authors, and this imagination is on full display in the stories of Your Utopia.

Buy a copy of Your Utopia here!

The Specters of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung

Translated by Yewon Jung

Separated into three acts and an epilogue, The Specters of Algeria begins with a girl named Yul, born during the military dictatorship of South Korea. Yul’s father is part of a theatre troupe, along with the father of her childhood friend Jing. We see the world through Yul’s eyes when the novel first begins.

Like with To Kill A Mockingbird, this naive perspective gives us a blinkered view of Yul’s world, but soon her friend Jing moves abroad and she grows up to own her own dress alteration business. Part two, set in th