If you’re wondering where to start with Japanese literature, these are the best Japanese books across sci-fi, mystery, literary fiction, and more.

Japanese literature is everywhere. The nation’s stories and novels get turned into manga, anime, and movies. Their authors are as famous and legendary as Hollywood’s actors and directors. And Japanese literature is big across the world.

The best Japanese books are often quick to be translated and, no matter how niche they may seem, they will find an audience. We at Books and Bao love the literature of Japan more than that of any other country, and Japanese authors have swum in the deep waters of every single genre.

Whether you’re looking for literary fiction, Japanese horror books, or Japanese mystery novels, you’ll find a few new favourites here amongst some of the best Japanese books of all time.

If you’ve always wondered where to start with Japanese literature, especially if you usually prefer a specific genre like romance, mystery, or fantasy, this guide to Japanese fiction will help you find the perfect book for you, whatever the genre.

Here, you’ll find twelve genres of Japanese literature, each with at least two unique Japanese book recommendations from us personally. Enjoy, and happy reading! If you want to stay up-to-date with the best new Japanese books every year, we’ve got you covered!

Classic Japanese Fiction

There are two meanings of the word ‘classic’ when it comes to fiction. There’s the official meaning, which is ‘any book that’s over 100 years old’ and then there’s the colloquial meaning which is, ‘anything the zeitgeist deems a classic’. So, for classic Japanese fiction, let’s have a bit of both.

Here, you’ll find some classic Japanese novels from times and eras long gone, and others from the last century which are now hailed as unparalleled modern classics of Japanese literature not to be missed. These, unsurprisingly, represent some of the best Japanese books around, full stop.

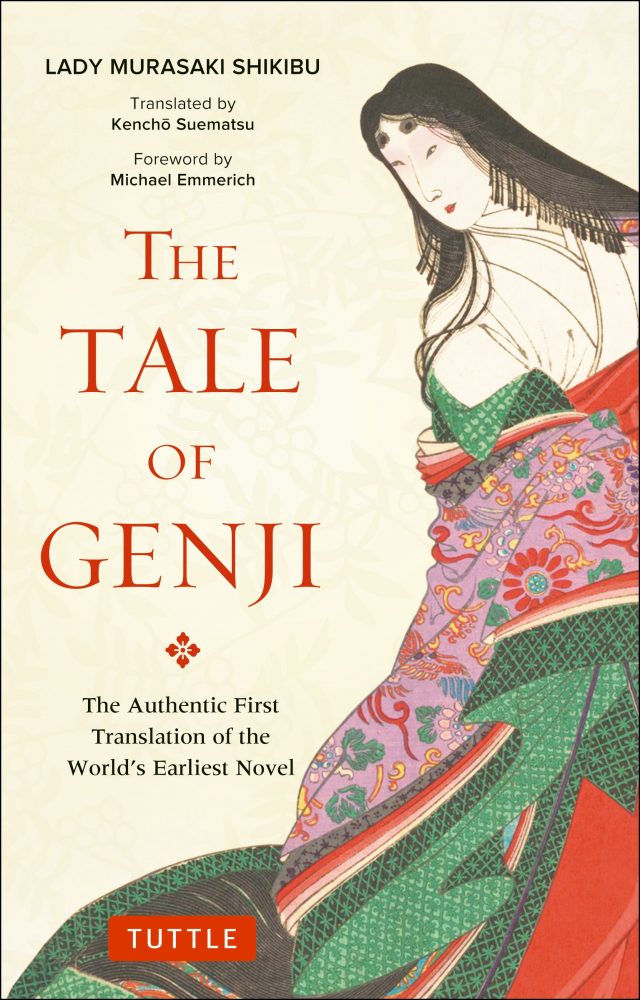

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu

Translated by Kencho Suematsu

The Tale of Genji has quite the legacy. Not only was it the first Japanese novel, but it is widely considered to be the first novel ever written anywhere in the world. That alone makes it one of the most important and best Japanese novels to read right now.

Written by the Kyoto noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century CE, The Tale of Genji takes us on a journey alongside the son of an emperor: Hikaru Genji. Genji is no longer in the line of succession and spends much of the novel’s story forming and then ruining relationships with various women in Kyoto.

The novel is a fascinating insight into the lives of Japan’s nobility back when Kyoto was the capital of Japan. It’s also a witty and smart novel that still holds up as one of the great works of classic Japanese fiction.

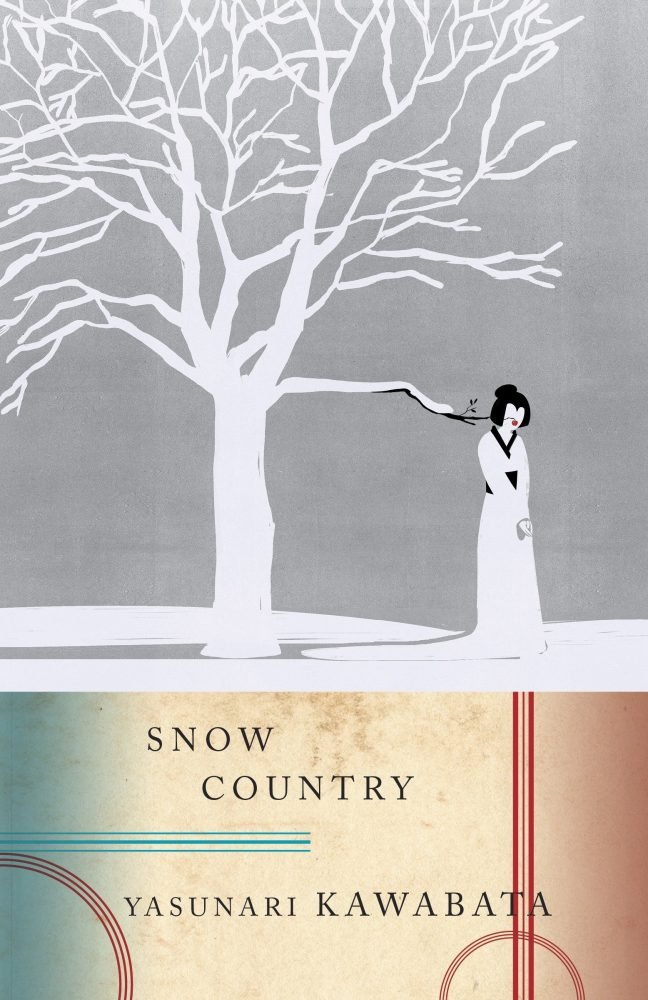

Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata

Translated by Edward G. Seidensticker

Many of his novels have the feel of a bell chime, opening with a loaded image that continues to resound throughout the rest of the story before drawing to a close with the final pages of the book.

For example, in his most famous work, Snow Country, the novel opens with a train ride through the mountainous countryside in which the narrator, staring out the window, superimposes the reflected face of a beautiful female passenger onto the darkening night sky and landscape outside.

Kawabata’s sparse yet wholly poetic opening is a masterstroke of foreshadowing in a novel that will confront the relationship between art, beauty, lust and love, in a near ethereal landscape, shown through a fragmented and sometimes drunken narration in which the main character finds himself unable to truly feel present and real before the beautiful geisha he has an affair with.

It reaches a harmony in the way the final image of the novel is of a brilliant moon hanging above that same night sky and illuminating the shocking climax. If you know anything about Japanese literature, you’ll know that Kawabata penned some of the best Japanese books of all time, and Snow Country may be his finest work.

(Taken from our Author Spotlight on Yasunari Kawabata)

The Silent Cry by Kenzaburo Oe

Translated by John Bester

Oe’s writing stems from his interactions with his own Japan, but while Ishiguro’s Japan is one somewhat fantastical, Oe’s is one of political turmoil, social struggle, and the fight for change. The Silent Cry tells the story of two brothers, the narrator and introverted academic Mitsusaburo, and his borderline-eccentric younger brother Takashi, who has just returned to Tokyo from New York.

After Mitsu and his wife make the choice to leave their handicapped infant child in an asylum, and Mitsu struggles with learning about the suicide of a friend (in a particularly and oddly erotic manner), he and his brother Takashi return to the village of their youth.

There, they do business and battle with a Korean slave-turned-CEO known as ‘the Emperor of Supermarkets’ who wishes to expand his empire. Just like Kawabata above, this Nobel Prize winner has authored some of the best Japanese books of the 20th Century, and The Silent Cry is the best place to start reading him.

(Taken from our article on Japan’s Nobel Prize Winners)

I Am a Cat by Natsume Soseki

Translated by Graeme Wilson

Natsume Soseki might be the most popular name in Japanese literature. When it comes to living authors, many first think of Haruki Murakami, but Soseki is certainly Japan’s most beloved author. He was a cynical man in many ways, and wrote novels that got to the faulty hearts of people in a sometimes earnest and sometimes cheeky way.

His cheekiest novel is a work of satire written from the perspective of a cat – I am a Cat. The cat spends the novel relaying to us the events that go on in his house, which mostly concern his owner, a teacher who does his best to appear proud and to fit in with the noble middle classes of early 20th century Japan.

If you want a real classic of Japanese fiction, any book by Soseki will do the trick, but I Am a Cat is without a doubt his most light-hearted and witty piece of fiction, though it is a bit on the long side.

As early 20th Century Japanese literature goes, I Am a Cat is one of the best Japanese books you can buy.

Read More: The Best Japanese Books of 2020

Japanese Literary Fiction

Literary fiction means different things to different people, but generally it is mature, thought-provoking, grounded fiction based in reality. And Japan has literary fiction to spare. Let’s look at some of the best Japanese books in the literary fiction genre by some of the best authors in Japan writing today.

Honeybees and Distant Thunder by Riku Onda

Riku Onda, author of The Aosawa Murders and Fish Swimming in Dappled Sunlight, explores the unique power of music to move the soul, bring out the best in us, and build community in her literary novel Honeybees and Distant Thunder.

This Japanese novel takes place over a single classical music competition, and we follow several protagonists — competing pianists and their judges — as they get to know themselves, each other, and their music. Riku Onda has crafted here a love letter to music itself. She shows us, with stark beauty, how music enriches and moves us, how it brings us together, and how it shows off the human capacity for creativity and artistic expression.

Our protagonists are young musicians with personal baggage, hopes and dreams, insecurities, and talents to explore. We come to feel so much for each of them, while developing a deep appreciation for the art they create. One of the most aesthetically beautiful Japanese novels you’ll ever read, Honeybees and Distant Thunder is a real masterpiece of Japanese literature.

Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai

Translated by Polly Barton

Mild Vertigo is a small but dense literary Japanese novel, originally written in the late ’90s, that presents us with a protagonist who is deeply compelling in her unremarkability. Natsumi is a middle class Tokyo housewife with two sons. Her life is defined by her routines, her familial and neighbourly connections, and her physical space.

We follow her along in these routines as she gossips, makes private observations, and loses herself in long trains of thought. Reminiscent of Lucy Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport, this is a novel that invites readers to become lost in the mind of an extraordinarily ordinary woman who takes pride in her busy but simple life.

It’s an intense read, demanding an incredible amount of focus as long paragraphs stretch across multiple pages and thoughts blur into one another, and then into actions and even conversations. It’s often difficult to tell where Natsumi’s interior and exterior worlds begin and end, as we become almost too intimate with her thoughts and behaviours, whilst also remaining at arm’s length.

As we get the feeling that we can never really know Natsumi, we have to wonder if she knows herself at all either. A staggering work of literary fiction, Mild Vertigo is one of the most unique and rewarding Japanese books of recent years.

Buy a copy of Mild Vertigo here!

The Premonition by Banana Yoshimoto

Translated by Asa Yoneda

Banana Yoshimoto is a revered mainstay of Japanese literature, her books cherished by readers around the world. Her 1988 literary novella The Premonition is a perfect example of why she is so beloved. This 100-page book follows a teenager named Yayoi, who has lived in peace and bliss with her parents and brother for, as far as she knows, her whole life.

But she also has a wayward and free-spirited young aunt whom she often likes to sneak out and visit. This aunt, Yukino, is a music teacher who has lived alone and lived her own way for several years. While visiting her aunt, Yayoi recovers hidden memories that reshape what she has come to understand about her childhood and her family.

This is a story not so much about an unreliable narrator, but a narrator with unreliable memories and perspectives. It’s also a story of love, compassion, and the malleability of relationships. A stunning piece of short literary fiction from the author of many of the best Japanese books of our time.

Buy a copy of The Premonition here!

In the Miso Soup by Ryu Murakami

Translated by Ralph McCarthy

Ryu Murakami is often, unfairly, and unflatteringly referred to as ‘the other Murakami’. He also happens to have written some of the darkest and best Japanese books of our time. His books are intensely clever and cynical examinations of the dark underbelly that always exists in Tokyo but rarely gets discussed in public or in the news. In The Miso Soup is a perfect example of exactly this.

Most of Murakami’s novels are set in and around the popular neon district of Shinjuku, where people shop, eat, and drink at all hours of the day. If you’ve ever played the Yakuza video games, this district is what Kamurocho was based off of.

As for In The Miso Soup, the novel concerns a young man named Kenji who works as a guide in Shinjuku, showing visitors all the best hangouts and nightlife. He sacrifices a night with his girlfriend in order to show around a strange foreigner who pays well but may harbour a dark secret.

Read More: Discover Kobe Abe – Japan’s Master of Surrealism

The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada

Translated by David Boyd

The Factory follows three protagonists who all work at an unspecified factory in Japan. The factory seems to make and distribute all manner of things and consumables, and its mass spans miles and miles.

A character remarks how the factory “really has it all, doesn’t it? Apartment complexes, supermarkets, a bowling alley, karaoke … It’s like a real town. It is. Much bigger than your average town, really … We’ve got our own shrine, with a priest and everything. All we’re missing now is a graveyard.”

And so, the factory has successfully become an inescapable place where humans live and work. Soon enough, they will die and be buried there. No longer can they separate home from work. No longer can they escape work. Work provides everything for them. The metaphor here is clear; it’s clever, it’s frightening, it’s Kafkaesque.

For fans of the surreal and the strange, as well as the works of Franz Kafka, The Factory is one of the best Japanese books you can get your hands on.

(Taken from our review of The Factory)

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri

Translated by Morgan Giles

Yu Miri was born in Japan to Korean parents, and as such is a South Korean citizen and occasional recipient of racist bias and abuse in Japan. Despite this, she has had a phenomenally successful career in Japan as both a playwright and a writer of prose.

Although born in Yokohama, Japan’s second largest city, she now lives in a small town in Fukushima, close to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant which suffered a meltdown following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami which claimed thousands of lives.

Kazu, the Tokyo Ueno Station’s protagonist, was born in the same year as Japan’s emperor, and both men’s sons were born on the same day. While the emperor was born into the height of privilege, Kazu was born in rural Fukushima, a place that would later be ravaged by destruction in 2011.

While the emperor’s son would go on to lead a healthy life, Kazu’s son’s would be cut short, and Kazu himself would live out his final days as one of the many homeless barely surviving in a village of tents in Ueno Park. The narrative of this exceptional novel tells the life of Kazu after death; his ghost haunts Ueno Park and often quietly observes the movements and conversations of strangers passing by.

These overheard conversations work as distractions which lead Kazu into, and then bring him back out of, flashbacks and memories of his wife, his son and daughter, and key events in his own life which are frequently tied to Ueno Station and the park. Honestly, Tokyo Ueno Station is one of our favourite Japanese books. It also happens to be one of the very best Japanese books every written, end of.

(Taken from our review of Tokyo Ueno Station)

Heaven by Mieko Kawakami

Translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd

Written by the author of the Japanese feminist masterpiece Breasts and Eggs (found below), and translated by the same outstanding translation team, Heaven is a monumental piece of Japanese literary fiction, and arguably one of the best Japanese books ever written.

The protagonist of Heaven is a nameless fourteen-year-old schoolboy who is bullied endlessly and viciously. He soon finds companionship in Kojima, a female classmate who is also bullied. The two form a friendship that is, in itself at times, toxic and problematic.

Heaven is a difficult read; it shines a light on the aggressive behaviour of children, the hostile world that is middle school and high school, the discomfort of loneliness and isolation.

Heaven is harrowing, distressing, difficult, and so much more. But it demands the reader’s attention and respect nonetheless. It encourages kindness by showing us how difficult life can be, especially for helpless young people who must go to school, and are charged with surviving it like an injured soldier on a battlefield.

Mieko Kawakami pulls no punches here. She exposes the dark hearts of bullies, and warns us of the cruelties of life. But learning the lessons she teaches us can encourage empathy, kindness, and community.

Heaven is a true masterpiece and one of the best Japanese books by one of the best Japanese authors in existence.

Watch our full review of Heaven here!

Finger Bone by Hiroki Takahashi

Translated by Takami Nieda

Novels about World War II are everywhere these days. Some are excellent; some are forgettable and even offensive. Finger Bone is one of those rare novels that transcends its genre. It’s a masterpiece of Japanese war fiction that encourages us to wrestle with that age-old question: where is the good in warfare?

It’s 1942, and our nameless protagonist is a young, Japanese soldier in Papua New Guinea. As this short novel progresses, we watch him make and lose friends, connect with frightened locals, and shrug off injury and illness. Taking place half in a field hospital and half in the thick of the jungle, Finger Bone is beautifully, harshly reminiscent of the poems of Wilfred Owen. A raw tale about the darkest, bleakest aspects of warfare.

This is about innocent men suffering fatal wounds, struggling to overcome malaria, forging bonds, and watching those bonds get severed without warning. At no point are politics discussed in real detail, and that’s what makes us ponder the grand purpose of war. All we see here are men suffering, and trying to keep their spirits high, as well as those of their friends and comrades.

Few war novels have such a raw, powerful, painful effect on the reader as Finger Bone does, and it does so in such a short space of time. Read it in one sitting, and it’ll change you forever.

Buy a copy of Finger Bone here!

The Woman in the Purple Skirt by Natsuko Imamura

Translated by Lucy North

Reminiscent of the Tom Waits song What’s He Building, this is a novel of paranoia told from the perspective of the paranoid person. The titular Woman in the Purple Skirt is our protagonist, but our narrator is someone known only as the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan.

Our narrator works at a Tokyo hotel, and she spends her days observing the life of the Woman in the Purple Skirt. Desperate to know her better, she uses social puppetry to land the Woman in the Purple Skirt a job at her hotel.

From here, we watch the Woman in the Purple Skirt flourish professionally and socially, while our narrator remains paranoid, envious, and invisible. She dreams of knowing, loving, and maybe even being, the Woman in the Purple Skirt.

Living in our narrator’s head is intoxicating and stressful in equal measure; increasingly so as this short Japanese novels grows and builds. You wonder how a book like this one can possibly end; what kind of conclusion it could possibly reach. This need drives you ever forward to reach the insane conclusion of one of the best Japanese books in translation of 2021.

Watch our full review of The Woman in the Purple Skirt here!

The Color of the Sky Is the Shape of the Heart by Chesil

Translated by Takami Nieda

The Color of the Sky Is the Shape of the Heart is an illuminating and heartbreaking novel inspired by the author’s own childhood. It tells the story of a Zainichi Korean (Korean citizens and their children, living and growing up in post-empire Japan).

Beginning in Oregon, where protagonist Ginny Park now lives, we are quickly taken back in time to her days at elementary and middle school in Japan, back when she was Jinhee. Jinhee was born of Zainichi Korean parents in Japan. She speaks Japanese and no Korean. She went to a Japanese elementary school and faced discrimination. At a Korean middle school, trouble finds her again.

Through short vignette-style chapters, we learn about Jinhee’s youth, her experiences, and the hardships endured by Zainichi Koreans in Japan every single day.

The Color of the Sky Is the Shape of the Heart is not an easy book to read, but it encourages so much love and empathy from the reader. It also sheds light on a subculture of Japanese people that are so seldom talked about, or even given a voice of their own.

What You Are Looking For Is in the Library by Michiko Aoyama

Translated by Alison Watts

This is an incredibly sweet, charming, and wholesome novel about feeling lost, and finding your way with the help and support of others.

Five chapters tell the stories of five people who all live in the same ward of Tokyo. A young sales assistant from the countryside, a man who dreams of owning his own business, a forty-year-old mother, an unemployed NEET, and a newly-retired man.

During each of their tales, these protagonists will visit their local library and meet Sayuri Komachi, a patient and kind librarian who will give them what books they want, as well as one extra book that will help them get unstuck.

These books always have nothing to do with the jobs, interests, and personalities of our characters. For example, our man who dreams of owning a business will be given a biology book on earthworms. But, upon reading these books, our protagonists will find inspiration and motivation; just enough to push them out of the fog they currently feel lost within.

The diversity of personality, situation, age, and background of each character adds so much variety and intrigue to this novel, and we are provided enough time to get to know them intimately. We become attached to them, worry for them, and hope that they will find a better life. With Sayuri’s help, we know that they will.

Thanks to some outstanding, funny, dynamic translation work from Alison Watts, What You Are Looking For Is in the Library is a truly unique, compelling, sweet, kind, and wholesome Japanese novel.

The Tatami Galaxy by Tomihiko Morimi

Translated by Emily Balistrieri

Across four acts, The Tatami Galaxy invites its readers to retread the same year in the life of a third-year university student in Kyoto. This is a Groundhog Day narrative that explores the what-ifs and maybes of life.

Each act begins in the same way, with the same opening page of description, and then the subtle changes come. The same supporting characters exist but his relationship to them is always different. In a way, we are searching for happiness or contentedness, or the secret to a “good” life. We watch him make mistakes and miss opportunities and then watch his life play out differently.

What remains the same throughout is him; he is still himself and his personality informs his decisions and actions. The Tatami Galaxy is a novel that is at once ambitious and simple. The characters and events are easy to follow, and yet there is a dreamlike quality to the narrative (and an actual god shows up early on). This is a book about life and what it means to live properly; and, of course, if any of that is even possible.

Idol, Burning by Rin Usami

Translated by Asa Yomeda

Written by a university student, this short and powerful Japanese novel won the 2020 Akutagawa Prize (Japan’s most prestigious literary prize). Idol, Burning is told from the perspective of a high school girl whose favourite idol, a member of an all-male idol group, has been hit with enormous social backlash after punching a female fan.

Her idol, Masaki, is Akari’s entire life. Her own mediocre existence offers her nothing special and her grades aren’t great, and so she projects every bit of excitement onto Masaki Ueno. This is a novel about idol culture and what it offer