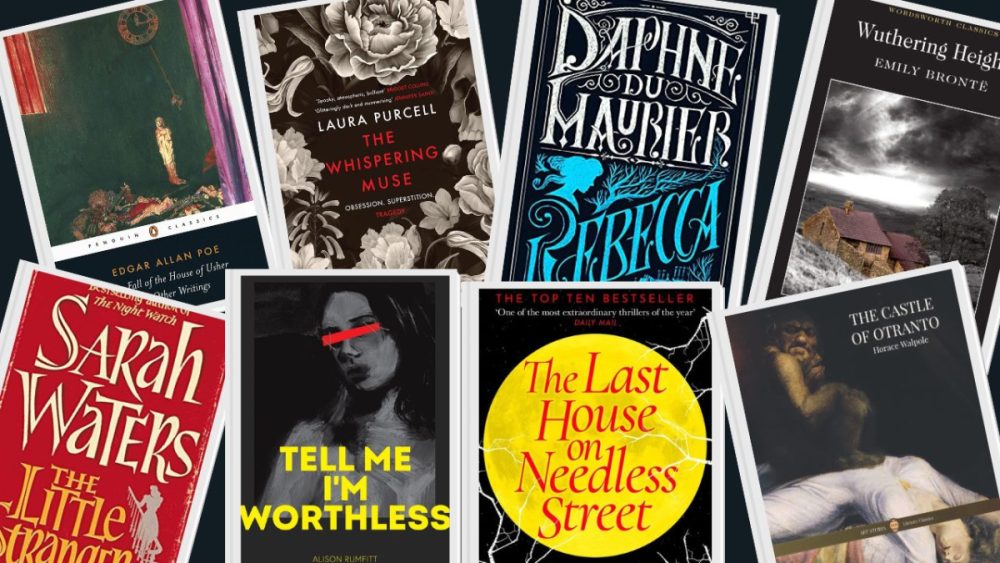

Literature has always served as a mirror to society’s deepest anxieties, reflecting cultural fears through metaphor and allegory. Just as Gothic fiction emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries as a response to industrialisation, channelling unease about scientific progress and urbanisation, today’s ecofiction grapples with the existential threats of climate change, mass extinction, and ecological collapse. These genres do more than tell stories; they crystallise our collective dread, forcing us to confront what haunts them most.

As a reader who loves both gothic and ecofiction, here are some of the genre’s defining novels, both classic and contemporary, what they have in common, and how the genre taps into our collective anxiety.

Why is ecofiction becoming more popular?

Ecofiction’s power lies in its ability to make the abstract tangible. Climate change is often discussed in terms of statistics, rising CO2 levels, shrinking ice caps, and increasing global temperatures, but these numbers can feel distant and impersonal. Or terrifying headlines that make us recoil and spend days in an existential loop. Literature bridges that gap for us by humanising ecological crises, enveloping them in narrative and metaphor that evoke empathy, dread, and, ideally, hope.

A good ecofiction novel can make extinction feel visceral. In Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, the sudden appearance of monarch butterflies in Appalachia due to disrupted migration patterns becomes a haunting metaphor for climate instability. The protagonist, Dellarobia, is not a scientist, but her bewilderment and grief mirror the reader’s own as she witnesses an ecological aberration that is both beautiful and tragic.

This is ecofiction’s strength; it transforms global issues into intimate, emotional experiences.

Much like the gothic genre took the Romantic era’s preoccupation with nature and tapped into its sublime wild unknowableness, pairing a romanticisation of the past with the anxiety of the current moment. Nature in ecofiction becomes an unstoppable, unknowable force, often a character in its own right. The past, though often romanticised, doesn’t hold off on the shortcomings of people and society.

Human ingenuity rarely triumphs over adversity in eco-fiction. Instead, it frequently presents nature as an indifferent or retaliatory force, exposing the hubris of human dominance. In doing so, it dismantles the illusion that we are separate from or superior to the ecosystems we inhabit. However by remembering that humans and our environment are one and the same also reminds us of our responsibility to protect the world around us.

The four defining narratives of ecofiction

Ecological anxiety tends to be explored in one of four ways in ecofiction. As this is a rapidly growing genre, it’s interesting to see how new stories build on these narratives and overlap with other genres like sci-fi and, more recently, solarpunk fiction. These are some of the common tropes and structures you’ll encounter in ecofiction.

1) The collapse narrative

Ecofiction, more often than not, depicts societal or environmental collapse, whether that’s sudden or gradual. Exploring how these communities adapt (or fail to adapt) to ecological disaster is key to the narrative.

From Paolo Bacigalupi’s drought-ravaged Southwest in The Water Knife to the submerged civilizations of Kirsty Logan’s The Gracekeepers, or the King Lear-inspired soggy London of Julia Armfield’s Private Rites, these stories test societal resilience post-collapse.

Matt Bell’s Appleseed uniquely layers three collapses: historical, imminent, and far-future, suggesting environmental destruction and human folly follow cyclical patterns. These narratives force readers to confront the fragility and ingenuity of civilization when pushed to its ecological limits.

2) The revenge of nature

Another common trope finds nature fighting back against human exploitation. In The Overstory by Richard Powers, trees are not passive resources but silent witnesses to human folly, their interconnectedness a rebuke to individualism—the novel suggests that nature’s resilience may outlast humanity’s destructive tendencies.

Jeff VanderMeer’s alien ecosystem in Annihilation, nature retaliates against exploitation, and the mythical rain-controlling bird in Robbie Arnott’s The Rain Heron embodies this trope most poetically, environmental balance restored through supernatural intervention.

3) The seer and the sceptic

Ecofiction often features characters who serve as ecological prophets, individuals who recognise environmental devastation before others do, and their struggle to be heard. In Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future dramatizes climate policy battles, while Silent Spring, though nonfiction, reads like ecofiction in its portrayal of Rachel Carson’s lonely crusade against pesticides.

In Charlotte McCoaghy’s Wild Dark Shore, a family struggles to preserve an Antarctic Seed Bank that faces destruction from rising sea levels, despite everyone else abandoning the island. This taps in so viscerally to the current moment where we feel powerless in the face of environmental and societal destruction.

4) The return to the wild

Some ecofictions explore rewilding, both literal and philosophical, as a response to ecological alienation. Barbara Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer to Marian Engel’s Bear, and narratives explore rewilding as an antidote to ecological alienation. The Gracekeepers and Private Rites extend this trope to cultural adaptation, its floating words developing new rituals for a flooded landscape, showing us fantasy alternatives to life beyond collapse.

Global Perspectives in Ecofiction: Beyond Anglo-American Narratives

While much of the popular contemporary ecofiction emerges from Western literary traditions, global perspectives offer rich, nuanced explorations of environmental challenges. Indigenous writers, in particular, bring profound ecological wisdom that challenges Western linear narratives of environmental destruction.

Latin American writers like Eduardo Galeano and Ailton Krenak weave environmental storytelling with anti-colonial narratives, and Brazilian author Krenak’s work, for instance, connects Indigenous worldviews with environmental resistance, presenting nature not as a resource to be managed, but as a living entity with intrinsic rights. Brazilian and Amazonian literature frequently challenges the extractive capitalism that threatens both ecological systems and Indigenous communities.

Nnedi Okorafor’s African futurist works, like Lagoon, reimagine ecological transformation through distinctly African perspectives, challenging Western sci-fi tropes and presenting environmental change as a potential site of regeneration rather than pure catastrophe.

Japanese author Yōko Ogawa’s The Memory Police subtly explores environmental loss through metaphorical disappearance, while Chinese writer Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem uses ecological destruction as a backdrop for complex philosophical inquiries about humanity’s place in the universe.

Despite its current popularity, ecofiction isn’t new

Ecofiction isn’t a new phenomenon. The gothic/sci-fi queen Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), often considered one of the first apocalyptic novels, imagines a world decimated by plague, reflecting early anxieties about human vulnerability. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) is an ecological novel in its depiction of Dust Bowl displacement, showing how environmental degradation and human suffering are intertwined.

In the latter half of the 20th century, works like Dune by Frank Herbert (1965) use science fiction to explore desertification and resource scarcity, while Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World Is Forest (1972) critiques colonialism and deforestation through an alien planet’s struggle against human invaders.

The enduring impact of gothic and ecofiction

Ecofiction does not always provide answers, but it asks the right questions: What have we lost? What can still be saved? And what does it mean to live ethically in a wounded world? These stories do more than warn; they reorient our imaginations toward alternative futures.

As rising ecological challenges reshape our world, ecofiction will likely continue to evolve. Apocalyptic warnings will likely become explorations of human-environment relationships, hopefully amplifying diverse global perspectives and offering imaginative pathways for understanding our collective ecological future.

Thank you for reading, please share this article if you found it interesting and check out our other bookish articles.